What is Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease where the articular cartilage—the smooth tissue covering the ends of bones—progressively deteriorates. This cartilage loss leads to the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs), joint space narrowing, and altered biomechanics, which can cause pain, swelling, and restricted joint mobility (Hunter & Bierma-Zeinstra, 2019). Knee OA is the most common type and is especially prevalent in older adults with Vos et al., (2020) reporting a global prevalence of 22.9% in individuals aged 40 and above.

Knee OA is classified into two categories:

- Primary OA: Occurs without an identifiable cause, commonly associated with age-related wear and tear.

- Secondary OA: Results from factors that disrupt joint biomechanics, such as trauma or underlying conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

Contributors to secondary OA include:

- Obesity

- Joint instability or hypermobility

- Malalignment (e.g., varus/valgus knees)

- Prior injury (e.g., meniscal tears or fractures)

- Joint immobilisation

- Genetic predisposition

- Abnormal movement patterns or biomechanical dysfunction (Katz et al., 2021)

What Causes the Cartilage to Wear Away?

Healthy cartilage depends on a well-balanced chemical environment within the joint. In OA, this balance is disrupted—typically by mechanical stress, inflammation, injury, or metabolic factors—leading to cartilage degradation. In osteoarthritis, the body releases certain chemicals called inflammatory cytokines, which act like messengers that trigger damage inside the joint. These chemicals cause the joint cells to produce enzymes that break down important building blocks of cartilage—like collagen (which provides strength) and proteoglycans (which help cartilage stay springy and absorb shock). As these building blocks are broken down, the cartilage becomes weaker and starts to wear away.

Who is Affected by Knee OA?

- OA is the leading cause of disability in older adults worldwide.

- Prevalence increases with age—especially after 40

- Women are more likely to develop knee OA than men, possibly due to hormonal and biomechanical differences (Felson et al., 2020)

- Approximately 13% of women and 10% of men over 60 have symptomatic knee OA

- After age 70, prevalence increases to around 40% (Hawker, 2019)

Diagnosis and Examination

When evaluating a person for knee osteoarthritis, the diagnostic process begins with a subjective history. Patients commonly describe pain during activities that load the joint, such as walking, standing, ascending or descending stairs, or rising from a chair. Morning stiffness or stiffness following periods of inactivity (e.g after sitting) are also typical, however stiffness tends to ease once movement resumes. Swelling may occur when inflammatory fluid accumulates within the joint. Some people may notice a sense of instability or their knee “giving way” due to poor muscle control. Over time, muscle weakness or a fear of movement can develop, further impacting mobility.

The objective examination builds on this history by focusing on observable signs and measurable deficits. Visual inspection may reveal swelling, muscle wasting, changes in knee alignment, or altered gait patterns. Hands-on assessment often uncovers tenderness along the joint line, warmth, or crepitus — a crackling sensation during movement. Range of motion is measured to detect any loss of range of motion or pain with movement. Functional tests, including sit-to-stand transitions or stair ambulation provide information on the impact of the patients OA on daily tasks.

Muscle strength testing identifies weaknesses in key muscle groups supporting the knee, particularly the quadriceps, hamstring, calf and gluteal muscles. Special tests help rule out ligament injuries, meniscal pathology or patellofemoral involvement, and a biomechanical assessment may identify issues in the hips, ankles, or foot posture that contribute to knee pain.

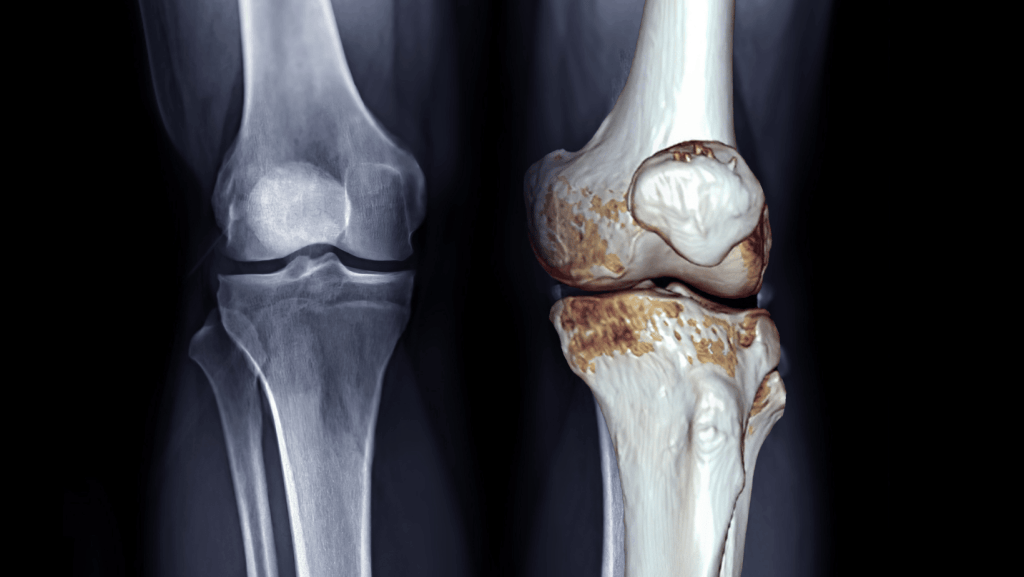

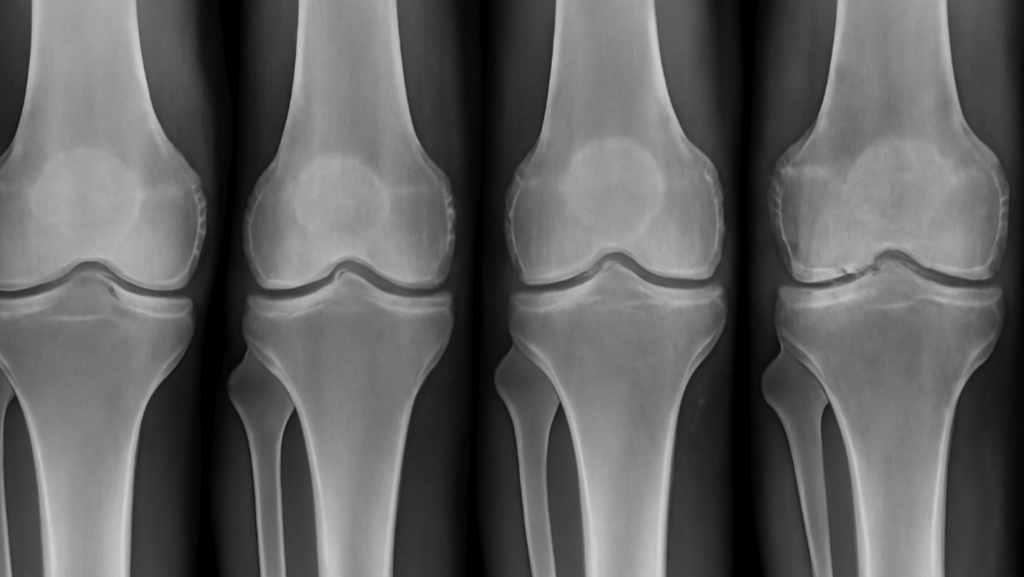

Imaging

Although imaging (X-rays or MRI) can confirm joint space narrowing, osteophytes, or additional pathology, they’re not always required as symptoms may not correlated with imaging findings. Recent literature by Deveza et al. (2023) found that up to 68% of people with radiographic OA had no symptoms or functional limitations.

Conservative Management of OA

Although OA can not be reversed, a tailored physiotherapy approach can improve various aspects of a patient’s quality of life (Hislop et al., 2020). The benefits and goals of physiotherapy include:

- Restore range of motion

- Reduce swelling and pain

- Improve muscle activation, strength and motor control

- Normalise gait and function

- Delay or avoid surgery

- Enhance independence and overall health

As part of physiotherapy assessment, the entire kinetic chain – the hip, knee, ankle and core is examined to evaluate for deficits in strength which may be contributing to knee OA symptoms. A 2020 meta-analysis (Hislop, et al.) found that stair ambulation, walking ability and sit-to-stand transition improved in patients with knee OA when prescribed with hip strengthening exercises. Furthermore, balance exercises prescribed for patients with knee OA also improves pain and function, reducing falls risk (Prabhakar, 2023).

Surgical Management of OA

Surgical intervention can be considered when conservative treatment no longer provides benefit. Surgical options include:

- Arthroscopy (less commonly recommended)

- High tibial osteotomy

- Partial (patellofemoral) arthroplasty

- Total knee arthroplasty (TKA)

Surgery may improve pain and function; however outcomes are heavily dependent on the quality of post-operative rehabilitation. Most surgeons recommend exhausting non-surgical options first unless the patient is significantly debilitated (Abbott et al., 2021).

Exercises that can help Knee OA

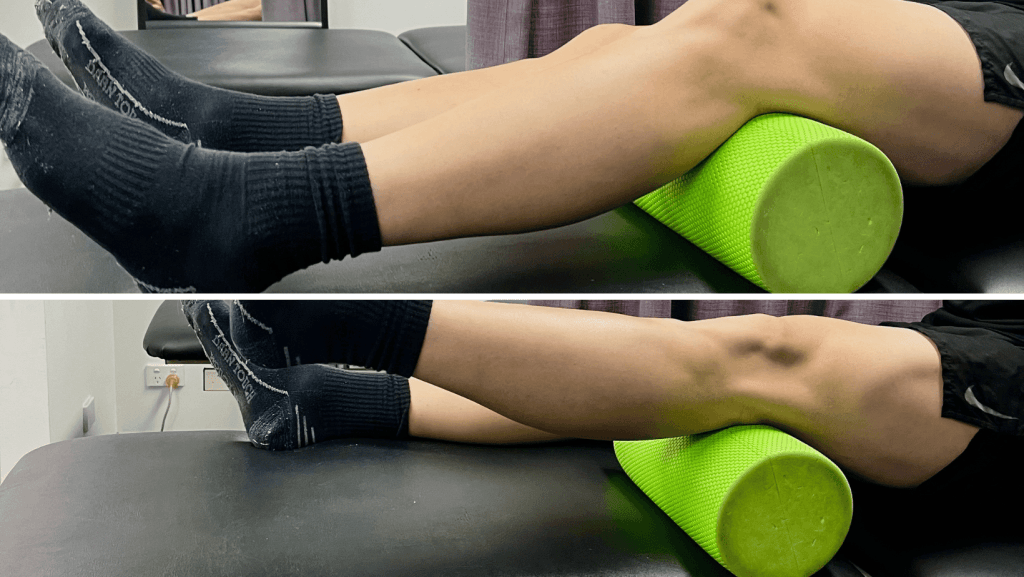

Inner Range Quad Exercise

Aim:Improve VMO and Quad strength and activation

How: Lying on you back or sitting up tall with a foam roller under your knee crease simply straighten your leg out, tensing the muscle at the top for 5 seconds. Repeat for reps.

Theraband TKE (Terminal Knee Extension)

Aim: Improve knee extension movement and improve walking gait. Important in the early stage of rehab when you can’t extend your knee.

How: Step through the loop of a theraband or powerband, placing it around your knee. Starting with a bent knee simply straighten out your knee, placing you heel on the ground using resistance from the band. This helps to get your knee straight. Hold for 3 -5 seconds. Repeat for reps.

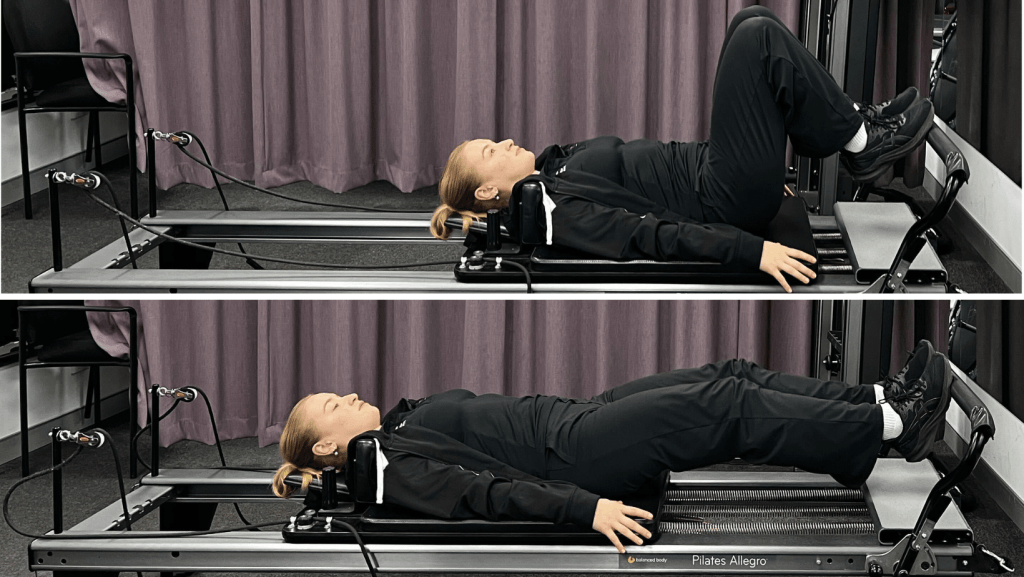

Squat using the Reformer

Aim: Improve lower limb strength in quads and glutes while keeping stress off your knees

How: Lay supine on the reformer with heels on the footbar. Push the carriage away ensuring your knees track in line with your toes. Pause and repeat for reps. Use a theraband around your knees to cue “pulling out” to ensure you engage your glute medius. Add springs for more resistance.

If you or someone you care for has an injury, a flare up, requires some rehabilitation or experiences an increase in pain, give the clinic a call on 9713 2455 or book online.